Opening Lines

J.V. Jones

Jan 23rd : 2008

|

Opening Lines

|

|

|

J.V. Jones

|

Jan 23rd : 2008

|

|

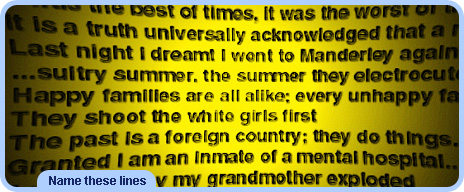

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.” “The sky above the port was the color of television tuned to a dead channel.” These three sentences mark the beginning of well known books (A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens, Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier, Neuromancer by William Gibson). All three are widely acknowledged to be great opening lines. Why? Because they capture our attention and make us want to read more. Dickens’ line intrigues us. Good and bad happening at the same time: How so? We read on to discover the answer. Du Maurier starts her tale up-and-running. We’re immediately in the head of the narrator, party to her most private thoughts. What is Manderley? Why does the narrator dream she was back there? Gibson does something different. He sets a sense of place and mood. Something’s wrong in the world--the sky is a symptom. What’s happening?  “It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.” This is the first sentence from George Orwell’s 1984. It shares similarities with Gibson's Neuromancer. Setting and mood are conveyed. Also, as with Gibson’s sky which is out-of-kilter, Orwell’s time is out of kilter. Both lines create a mysterious and unique sense of foreboding. The ‘mysterious setting’ beginning can be difficult to do well. It’s description, not action. So it’s passive, and the writing has to be sharp to counteract this. Something has to be unique--a metaphor, an observation, a detail--as well being interesting. “It was about eleven o'clock in the morning, mid October, with the sun not shining and a look of hard wet rain in the clearness of the foothills.” Chandler’s The Big Sleep accomplishes this with an unusual negative: the sun not shining. Most writers would say it’s cloudy. By highlighting what’s not there, Chandler spikes the sentence and draws us in to a world where something’s missing right from the start. “There was no possibility of taking a walk that day.” Jane Eyre. “Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents.” Little Women. “It began as a mistake.” Bukowski’s Post Office. All begin with a single statement that makes us want to understand the reason behind it. The ‘intriguing statement’ beginning is one of the easiest for beginning writers to learn. We just need to reproduce our own version of it. “That Sunday we didn’t go to church.” Or, “No one could recall the last time the lake froze in September.” It’s worthwhile practicing this as it helps pinpoint the moment your story begins. More on beginning lines next week. |